Editor's note: CGTN's First Voice provides instant commentary on breaking stories. The column clarifies emerging issues and better defines the news agenda, offering a Chinese perspective on the latest global events.

By Jiang Shisong

According to U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the U.S. wants to "de-risk and diversify" its relationship with China, not decouple. He said the U.S. is not seeking confrontation or conflict with China but cooperation on common challenges such as climate change, pandemic prevention, and nuclear non-proliferation. In effect, the U.S. and its allies are increasingly adopting a new term to describe their approach to China: de-risking. This means reducing their dependence and vulnerability to China's economic and political influence without completely cutting off ties or cooperation.

De-risking with China emerged as a strategic move when European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen mentioned it before her visit to Beijing last April, along with French President Emmanuel Macron. She emphasized that "it is neither viable – nor in Europe's interest – to decouple from China. Our relations are not black or white – and our response cannot be either. This is why we need to focus on de-risk – not de-couple."

At first glance, de-risking sounds acceptable for dealing with a rising China and particularly good for already strained China-U.S. relations. It seems to imply a balanced approach that avoids extremes of either appeasement or containment. But, in reality, it is no more than a disguised form of decoupling and protectionism in the service of the current geopolitical landscape by, among others, reducing the opportunities and channels for dialogue, cooperation, and engagement with China. Premised on distorting and exaggerating the perception of China as a threat to security and values, the bloc in question is trying to use this approach to contain China's development and preserve its own dominance in the global economic and political system.

On the surface, the so-called "de-risking" strategy seems to only avoid and reduce certain risks associated with engaging with China, while pursuing some level of cooperation and interaction in areas of common interest. Then, what are the risks that make U.S. and EU political elites fearful and anxious? Von der Leyen summarized eight major risks, which are nothing but imaginary human rights violations, speculative military ambitions, and maliciously depicted technological competition.

She completely ignores China's outstanding contributions to human rights protection, global and regional security and stability, and scientific and technological development. Also, she undermines the enormous human value that friendly cooperation with China in these areas can bring. So, the risks of "de-risking" towards China not only do not exist at all, but should be the focus of cooperation.

To a large extent, taking the "de-risking" strategy towards China will likely have counterproductive effects, increasing chances of misunderstanding, miscalculations, and conflicts among Beijing, Washington, and Brussels. In addition, it may also pose hazards to the world, including exacerbating global economic inequality, increasing geopolitical risks, harming the global environment, and undermining global governance.

These economic and political harms of de-risking have actually gained attention from many, but less consideration has been given to the legal components of this strategy. As the initiator, the EU actually empowered its de-risking strategy by introducing a series of legislative acts and proposals that the European Commission has put forward or plans to put forward as part of its strategy to de-risk its relations with China and strengthen its economic security and resilience.

These legal components include enhancing legislation such as the Net-Zero Industry Act and Critical Raw Materials Act. Each of these statutes aims to reduce the EU's dependency on China in various sectors by specifically restricting and tightening the screening of Chinese investments in critical infrastructure and technologies. In essence, these legislative measures reflect a protectionist approach that prioritizes the EU's economic interests and security over its engagement with China.

Also, these legal components can have implications for international trade and investment rules and might lead to potential accusations of infringement on the WTO principle of non-discrimination, as they single out Chinese entities for scrutiny, which can be seen as discriminatory.

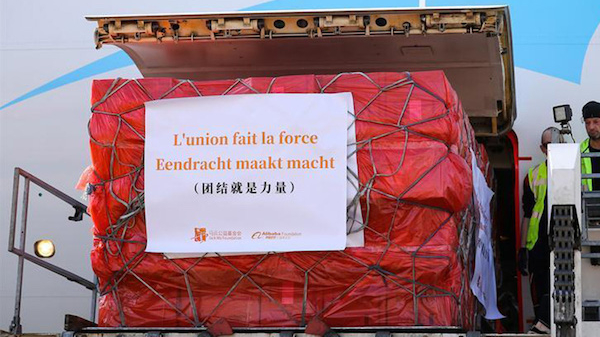

China-donated medical equipment with a banner on its package saying "Unity is power" written in French, Dutch and Chinese is seen arriving at Liege Airport, Belgium, March 16, 2020. [Photo/Xinhua]

Besides, the EU is also exploring several trade deals and partnerships with countries and regions such as New Zealand, Australia and ASEAN. The objective is to enhance the EU's supply chain resilience and diversify its trade. But, these agreements can also be perceived as an attempt to isolate China and limit its economic influence in the global market. Such isolationist policies can lead to a reduced market for EU goods and services and limit opportunities for cooperation with China on global economic issues.

In addition, although the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) was agreed in principle in December 2020, it was put on hold in 2021 after China retaliated with sanctions against several EU lawmakers in response to the bloc's ungrounded sanctions. The absence of discussion about the CAI during von der Leyen's recent meeting with President Xi Jinping has raised concerns the agreement may not be resumed at all. Without the CAI in place, both parties risk missing out on the economic benefits of increased market access and a level playing field for businesses. Such a scenario could only bring the EU closer to the American-style protectionist line on China.

De-risking is not merely a political maneuver but rather a complex legal strategy that plays a critical role in the EU's efforts to recalibrate its relationship with China. So, it is crucial to approach this issue with caution and carefully consider its legal implications and underlying motives, rather than simply assuming an ostensible shift from decoupling to de-risking. Thinking in this way, the U.S. has taken similar yet more aggressive steps to pursue the legal components of de-risking.

Thus, existing U.S. legislation that originally entailed decoupling measures will be repackaged as de-risking measures. Due to their new, generic name, these measures will slip under the radar and be perceived as more benign and less confrontational than they actually are. Moreover, new legislation targeting China may follow suit, further complicating the legal implications of de-risking.

Trust is the bedrock of successful international collaboration, and its importance cannot be overemphasized. While de-risking may seem preferable to decoupling, politicizing legal measures in pursuit of such a strategy risks fraying the already fragile trust among nations during a period of crisis and unprecedented change. As a result, China and other countries must not be deceived by this new concept of de-risking and should make necessary legal preparations accordingly.

This First Voice article is written by CGTN Special Commentator Jiang Shisong, a research fellow with the School of Law, Chongqing University.

中文

中文