By Abu Naser Al Farabi

In its high-handed geo-economic statecraft "to maintain as large of a lead as possible," as U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan put it earlier; and freeze China's advanced chip production and supercomputing capabilities, the Biden administration in October last year imposed a series of technological export controls on China. Since then, such restrictions, both unilateral and extraterritorial in nature, have continued to receive backlash from the parties across the semiconductor ecosystem and whom the United States has been striving to drag down into its decoupling campaign.

After the Netherlands' ASML Holding NV Chief Executive Officer Peter Wennink had warned excessive control measures could lead to higher costs for chipmakers, affecting chip availability, and the semiconductor supply chain, Reuters reported that Dutch and U.S. officials met in Washington on January 27 to discuss potential new controls on exporting semiconductor manufacturing gear to China. The report further claimed a deal could be announced by the end of the month based on the sources' information.

It is the latest in U.S.'s months-long effort to strong-arm its European and East Asian allies, more particularly the Netherlands and Japan, into its aggressive technological warfare against China. Biden's techno-centric warfare is in a broad sense an economic warfare waged against China, mostly out of its desperation to salvage its hegemonic economic edge over its "competitor," China.

The current tech war against China is reminiscent of what Washington pursued in the 1980s against Japan. But its semiconductor control measures against China are somewhat distinct in the sense that it has been built on a misguided conception about the very nature of the global technological ecosystem and the over-appreciation of U.S. power to coerce the system into running in line with its strategic objectives.

The Biden administration seems so far to have adopted a two-pronged strategy in its techno-nationalist approach to China. On one hand, it has weaponized its privileged vestige in the global technology supply chain, especially through its "foreign direct product rule" provisions that allow the United States to apply controls extraterritorially in certain circumstances, such as forcing companies outside the United States to not sell semiconductors to China if they were produced using U.S. equipment. On the other hand, it has been in a frenzied on-shoring rush to reenergize its own technological and industrial position in apparent blows to the free and open international trade system and at the monumental cost of countries, both its allies and perceived enemies.

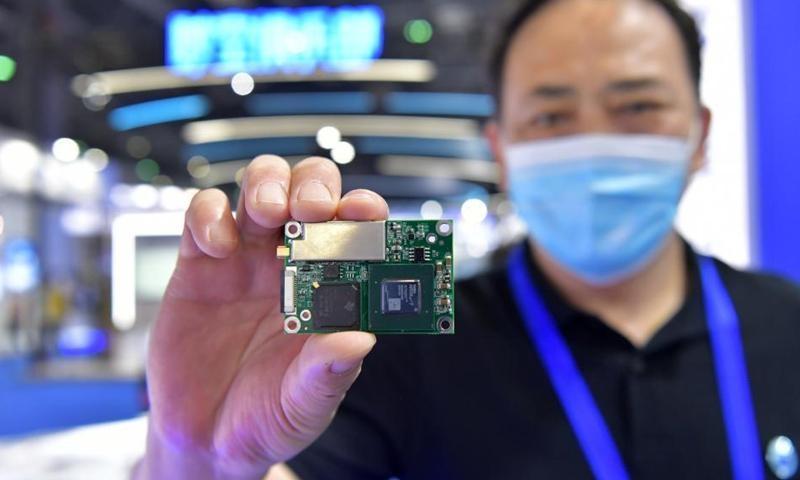

An exhibitor shows a module with an anti-jamming chip during the 12th China Satellite Navigation Expo (CSNE) in Nanchang, capital of east China's Jiangxi Province, May 27, 2021. [Photo/Xinhua]

Washington's recent semiconductor export controls on China have stemmed from its misconceived notion about its dominance in the semiconductor supply chain network. The techno-nationalist policy planners in Washington have drawn faulty analogies from its centrality in the global financial system, imagining that the supremacy of the dollar offers parallelism for the country's position in the global semiconductor supply chain.

It's true that the United States still enjoys substantial advantage within the hierarchical global financial network and still can exploit its position to achieve its geopolitical objective. The U.S.'s sanctions strategy is based on this premise. But It has not been without wider discontent, disability, or even backlash. Decades-long unilateral, extraterritorial, exploitative and geopolitical motives-driven use of this sacrosanct centrality is compelling a host of countries to counterbalance U.S. dollar dominance.

Previously, it was widely perceived that reorientation from the dollar-dominant global financial system to an alternative currency would be near impossible. In March 2022, a report released by the International Monetary Fund entitled "The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance" showed that the share of reserves held in U.S. dollars by central banks dropped by 12 percentage points since the turn of the century, from 71 percent in 1999 to 59 percent in 2021,as central banks around the world have been diversifying their portfolios with other currencies, including Chinese yuan.

Several countries have greater control over specific parts of the supply chain than do others, but no one nation controls the entire network. U.S. dominance in the complex chips network is highly overblown, as only 12 percent of the world's chips are produced in the United States. Moreover, the raw materials required to make microchips are equally concentrated in a handful of nations, notably China. That is why the U.S. position in the advanced technology supply is more contingent and more vulnerable to shocks than its dominance in global finance.

Most Importantly, given the underlying structure and inherently adaptive nature to shifts over time, technology supply chains can be adapted and reorganized more easily than the dollar-based financial system. It is no denying that export controls would put substantial costs on China in the short term, but it will certainly prove blunt over time. China will not have to reconfigure the whole network except for certain nodes within it.

Given that the semiconductor industry is highly competitive in nature, and technology advances swiftly, countries or firms can make new breakthroughs both by creating more sophisticated chips and discovering more dependable and efficient production techniques. And given China's already solid foundation in tech, indigenous innovation capabilities, the highly active presence of tech start-up culture, and increasing public and private investments in the sector, it is highly likely that U.S. efforts to stymie China's tech advancement will fall flat in the long run.

For others having competitive edges with the semiconductors networks and being forced to goad into U.S. nefarious strategic lines against China, it must be remembered that the sustainability of their specific competitive advantage in the semiconductor supply chain is highly contingent on the continuous competition. The weaponization of privileged positions, as previous cases suggest, will only lead to deterioration.

Abu Naser Al Farabi is a Dhaka-based columnist and analyst focusing on international politics, especially Asian affairs.

中文

中文