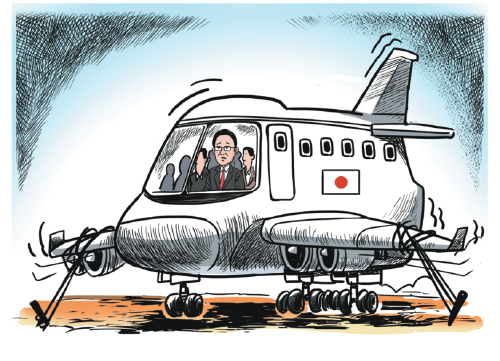

[Photo by Shi Yu/China Daily]

By Yin Xiaoliang

Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party leader Fumio Kishida took office as the country's 100th prime minister on Oct 4, but his government will not be in office for even one month as he has called the general election on Oct 31.

Nevertheless, it is worth analyzing the features that differentiate the Kishida administration from the previous ones in the past 20 years. The Kishida Cabinet has 20 new faces, 13 of whom have never been in the Japanese Cabinet. Also, nine of them are aged below 60, and only Takayuki Kobayashi, Karen Makishima and Noriko Horiuchi have been members of the lower house before.

Kishida inducted new faces in his Cabinet to change the image of the LDP, cultivate new political talents and fulfill the promise he made while running for the LDP's top post.

But in just two weeks into his prime ministership, Kishida sent a ritual offering to the Yasukuni Shrine, which honors 14 class-A war criminals, for the autumn festival, indicating the new Japanese administration will not take a different attitude from previous cabinets toward history and the country's militarist past.

Forty-six-year-old Kobayashi, the vice-minister of defense in the Shinzo Abe administration, was included in the new Cabinet as Japan's first economic security minister, and will be in charge of cyber security, technology exports, national economic security projects and technologies. Following Abe's policies, the new administration created the post apparently to maximize Japan's economic and security benefits amid rising Sino-US competition. But many analysts say the ministry has been created to work with the United States to counter China and thus poses a big challenge to China-Japan ties.

In his first policy speech on Oct 8, Kishida vowed to boost Japan's economic growth with a "new form of capitalism" and use its fruits to expand the country's middle class. Which means he intends to change, even replace "Abenomics", which failed to improve the Japanese people's livelihoods and instead widened the rich-poor gap.

In reality, the Kishida administration has set a "new" agenda to solve "old" problems. It faces a raft of challenges both on the domestic and foreign fronts including deflationary pressure due to the stratification of wealth, the COVID-19 pandemic, and a low birthrate and an aging population-and the strained Sino-Japanese relations.

A country's foreign policy is generally regarded as an extension of its domestic policy. Yet the two policies can be complementary and interactive to a certain extent. A good diplomatic strategy can compensate for a poor domestic policy. Hence, Japan's relations with China are not only about peace, stability and prosperity in the region and beyond, but also about the Kishida administration's ability to achieve its domestic political goals.

The Japanese government has three choices-establish friendly relations with China; counter China; or follow and strengthen Abe's policy to stabilize China-Japan ties. Many expect Kishida to stabilize China-Japan ties, given his political experience and Japan's factional politics.

As a veteran politician, Kishida is widely seen as an able leader. He was included in the Abe Cabinet as foreign minister in 2012, and played a key role in the signing of the "comfort women" agreement between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 2015, and helped arrange former US president Barack Obama's visit to Hiroshima in 2016.

Besides, Kishida is the leader of the LDP's Kochikai (Broad Pond Society) faction that supports making moderate efforts to reduce the income gap in the country, and strengthening the social safety net in a way that doesn't hamper economic growth. And since the Kochikai faction also supports a dovish foreign policy, Kishida has stressed the importance of regularly communicating with China and stabilizing Sino-Japanese ties.

Yet Kishida also hyped up the Taiwan question during the LDP's presidential election campaign, and on Sunday sent a ritual offering to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine.

Factional politics played a decisive role in Kishida winning the LDP's top post. Within the LDP, different factions support each other due to mutual interest, not because they have similar political agendas. And since Kishida couldn't have won the LDP presidential election without the support of other factions, many members in his Cabinet are Abe supporters.

In other words, factional politics and conservative groups in the LDP will hamper Kishida's foreign and domestic agendas. So Kishida is not likely to veer significantly from the Abe administration's policy toward China even if he wins the Oct 31 general election, yet he is not likely to indulge in zero-sum games.

Besides, the US-Japan alliance restrains Japan to some extent from developing truly friendly relations with China.

China-US relations have deteriorated in recent years, and the Joe Biden administration is forging new or strengthening existing alliances to counter China's influence in Asia. Against this backdrop, Japan can hardly adopt a truly independent foreign policy. But by trying to isolate China from regional trade, Japan will harm its own interests because China is Japan's largest trading partner.

Japan's postwar diplomacy has been shaped by the United Nations Charter, the US-Japan alliance and what can be called Asian diplomacy. If Kishida focuses only on strengthening the US-Japan alliance even after winning the Oct 31 election, he will end up confining Japan in many fields, including trade. But he will win more support from the LDP and the public if he stabilizes relations with China.

And since Japan does not have the capability to counter China, the Kishida administration's best choice would be to build a stable and pragmatic Sino-Japanese relationship, in order to boost Japan's economy and narrow the wealth gap in the country.

The author is a professor at the Institute of Japanese Studies, Nankai University.

中文

中文